NOTE: This page was last updated: 9/20/20. Portions of the text that relevant to current market conditions (which are in Italic typeface) will be updated as needed.

It’s tempting to see fixed income as a singular asset class that serves as a lower-risk/lower reward counterpoint to equities. In a high-level sense, that’s true. Less often recognized, however, is that like equities, fixed-income consists of many subcategories and requires a protocol for choosing that, although different from equities, is every bit as important; perhaps even more so since fixed-income investors tend, on the whole, to be less inclined to take risk and therefor likely to be less tolerant of what later turn out to have been bad decisions.

Fixed Income ETFs Differ Materially From Fixed Income Securities

The challenges are magnified when we move from individual fixed-income securities to fixed-income ETFs.

- Individual securities have contractually established payment obligations at maturity, potential calls (occasions when the issuer/borrower is allowed to accelerate maturity to an earlier date) and with respect to payment of interest, which is usually twice per year.

- ETFs are portfolios of securities that are, for the most part, designed to have perpetual life (the exception being a so-far still-small set of fixed-maturity ETFs). So, for example, an ETF targeting a 7- to-10 year maturity will persist long beyond any 10-year time period. When portfolio securities age to the point where there is not enough time left to maturity, they get sold and replaced by others with more time left. This means that some of the most intricate bond math used to manage fixed-income risk do not work for ETFs the way they do for individual securities. In a practical sense, these differences can add to return during times of persistent falling rates, but if we move to an environment of persistent rate increases, they have the potential to exacerbate secondary-market risk.

The Benefits Of Using ETFs To Invest In Fixed Income

Despite the increased complexity, there are good reasons for many investors to prefer ETFs to individual fixed-income securities.

- The fixed-income market is heavily inhabited by investors, often institutional, who buy securities and plant to hold them to maturity, often pursuing strategies designed more to achieve targeted cash flows (to fund pension payments, for example) rather than maximize returns absolutely of versus a benchmark. That means that with the exception of US Treasury securities, the fixed-income market is far less liquid than anything the typical equity investor would deem acceptable. It means mutual fund and ETF Net Asset Values are based on mathematical estimates rather observed market activity, a system that usually works fine but which can cause unusual volatility in times of crisis. It also means standard lot sizes are bigger: This is not to say smaller non-institutional lot sizes can’t be traded but bid-ask spreads are likely to be less friendly to odd-lot orders. Use of ETFs allows investors to mitigate these problems.

- ETFs are far superior in terms of the way they enable the typical investor to reinvest interest and thereby earn interest-on-interest. This can be a major component of total return, especially if interest rates transition to an up-cycle. The price trend for of the ETF may look lackluster or poor, but but the investor’s account may trend much better as the price, such as it is, gets continually multiplied by more and more shares. And during periods of rising rates, these new shares will have been purchased at lower prices, meaning the investor is continually averaging down. Its much harder for non-institutional investors to benefit from this since (a) individual securities pay interest twice per year while the typically ETF pay monthly, and (b) it’s much easier to quickly re-deploy ETF dividends toward reinvestment than it is for holders of individual securities seeking to reinvest interest in smaller lots.

So fixed-income ETFs can play a valuable role in a portfolio — just as many advisors presume when they used equity/fixed income allocations such as the popular 60/40 standard with variations established to accommodate differing client risk profiles.

But for truly effective execution, it’s important to recognize the unique characteristics of fixed-income ETFs and make thoughtful choices, just as with equities. From 1982 through 2020, with interest rates having pushed lower and lower and lower, it was easy to make mistakes and feel no punishment (other than, perhaps, the unseen unthought-of “opportunity losses” due to failure to have performed stupendously as opposed to merely magnificently). Times have changed. Gong forward, expect to see bad choices punished in the marketplace absolutely, not just through theoretical missed opportunities.

To assist investors and advisors in navigating the varied, challenging and often-misunderstood world for fixed-income ETFs, I’ll go through a step-by-step decision sequence that should guide any search involving this asset class.

An 8-Step Fixed-Income ETF Selection Process

Yield, which is the thing many focus on exclusively, is not Step 1. We’ll get to it in Step 4. I love yield as much as anybody and I work hard to get it in my personal portfolio. But the risk-profile that typically motivates exposure to fixed income mandates that our yield goals and expectations be conditioned by the kinds of risks we’re willing to take, lest we later look back with regret on choices that seemed appealing on day one (as often happens to “yield hogs” who fail to properly account for risk).

Step 1: Manage Expectations

Actually, sensible expectations are important for everything, but fixed-income today poses some unique challenges. When it comes to choosing within the fixed-income field, I won’t merely recite the script about past performance not assuring future outcomes. Fixed-income investors need to edit it to say something like: If there’s one thing we can be darn sure of it’s that future outcomes will look absolutely nothing like past performance and may even turn out 180-degrees opposite.

After 40-or so years of relentless interest-rate declines, we’ve pretty much hit the upper limit of fixed income asset valuations, which are defined by interest rates at zero.

Yes, yes I know all about the talk of rates going negative. But this isn’t a bona fide investment case: It’s about an extreme and rare effort to push financial institutions to refrain from holding “excess” reserves and to lend the money out (or at the edge of an extreme, an effort to push consumers to reduce saving and do more spending). The idea is to prevent institutions from earning a return on reserves (even a minimal return) and to effectively force them to pay a fee for the right to remain as liquid as they wish. So while negative rates can and do exist on occasion, do not think of this in a way that would allow investors in fixed-income securities to continue to enjoy the buoyant capital gains to which they had become accustomed almost continually since 1982. And don’t by any means dream about getting a notification from Visa, MasterCard or Amex that they’ll pay you at an annual rate of 8% if only you’d choose to keep you balances high and outstanding. Ditto fantasies about mortgage lenders bidding against one another to see who can offer you to pay you the highest annual rate if only you’d be willing to take their money off their hands for thirty years.

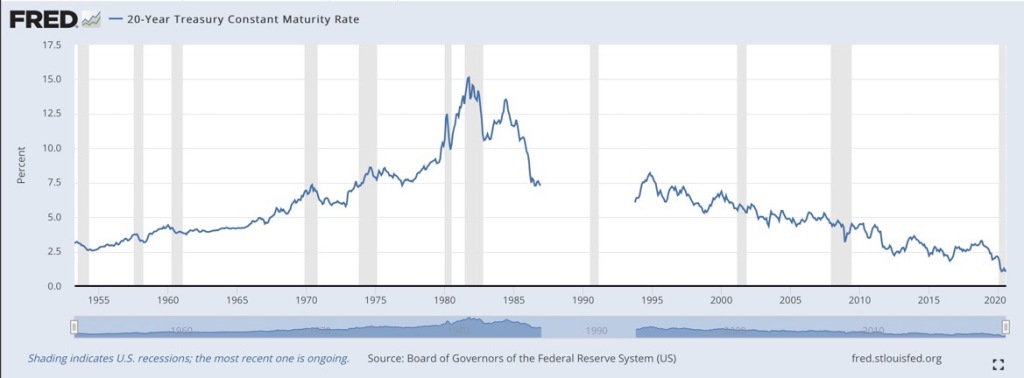

Closer to home (at least in terms of fixed-income investing) take a look at a long-term price chart for the the US 20- Year Treasury (the gap reflects a time when the Treasury didn’t issue 20-year paper) and the performance of the iShares 20+ Year Treasury (TLT) (ETF Home), one of the major beneficiaries of declining interest rates: Enjoy it, frame it, and prepare to reminisce because things will look a lot different going forward.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US), 20-Year Treasury Constant Maturity Rate [GS20], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/GS20, Sep. 1, 2020

A long-term trend such as this cannot and will not continue. While fixed-income capital gains can still happen as the Fed continues its floor-it covid-era monetary stance, know that this is not something on which we can continue to count. Zigs and zags in the context of a generally horizontal trading range is the best case scenario at this time. And capital gains now are for traders, not investors.

Chart courtesy of StockCharts.com

Step 2: Make Choices Regarding Term

Based on what I said above with respect to expectations, the choice of term is an exceptionally sensitive one. If you choose something longer than a very short, short, or maybe modestly intermediate term. be extra vigilant about the yield premium (if any) you stand to get in order to compensate you for term risk, that is the risk that future increases in interest rates will depress the market values of the securities in the ETF portfolio. Remember, in an ETF, these securities will usually be sold at some point into secondary market. Don’t expect holding to maturity to bail you out.

Just recently, the FED expressed its intent to refrain from raising rates until 2023. But don’t get complacent about chasing tiny yield premiums available on longer-dated issues. Just because the FED expresses an intent does mean its an accomplishment-in-fact. Even if we’ve already seen the worst of the Covid crisis, it looks like we’re still facing heavy fiscal -policy demands and greater deficit spending.So much the more so if the Democrats capture the White House in November or strengthen themselves in Congress. So far, excess liquidity being pumped into the economy has been largely sucked up into the prices of financial assets. Whether that shifts toward physical assets (i.e. inflation as conventionally defined) is more a political matter than an economic consideration. So the upcoming election poses huge risks.

There is, however, and important and potentially appealing exception; defined maturity ETFs, referred to by some issuers as “bullet shares.” This is an ETF that holds securities that are scheduled to mature at a specifically-stated time. Absent adverse credit problems (most are high grade though there are some lower-quality offering out there — be observant), the ETF will receive 100 cents to the dollar on that date and distribute the proceeds to shareholders. The ETF will then liquidate. Don’t fret about red tape. If you don’t sell in advance of the liquidation, then you’ll simply see the ETF vanish from the Holdings presentation of your brokerage account and the cash inflow reflected in the Transaction History, often labeled by the firm as a Sale.

This can make for an interesting way for you to managed your term risk through a “ladder” strategy. Here, you divide your fixed-income stake among several bullet shares of varying maturities. As the shortest one matures, or is sold by you before maturity/liquidation, you reinvest those funds in a new Bullet Shares ETF scheduled to mature later than the longest-dated one you currently hold. (Anticipating and facilitating ladder strategies, these ETF stretch the series each year by offering a new, longer dated ETF. Click here for more on laddering.

Step 3: Make Choices About Credit/Issuer Type

For purposes of published commentary, I always eliminate Municipals up front. I do this because the unique aspects of the investment case, the tradeoff between a lesser — all else being equal — return without taxes versus a higher taxable return is something each investor has to address individually, perhaps with the help of a tax adviser. If Municipals make sense for your individual situation evaluate them the way you would any other issue except you’ll want to take particular note of credit quality, which is sensitive not to corporate fundamentals but to the ability of local entities to fund obligations, whether through normal cash streams, tax increases, levies, subsidies from other public entities, etc. Be aware, too, that some issuers are fully protected by the full faith and credit of a another, typically higher-level, public entity. But then, you’d still subject to potential problems on the part of the guaranteeing entity. It’s also possible that some municipal issues may be protected by private insurance. Whatever you do, do not take this area lightly. There’s need for serious research here, especially since most municipal ETFs are widely diversified between states and entireties, thereby increasing the homework load.

Given zero-credit risk, it would be wonderful to be able to load up on Treasuries, which have been multi-decade market mega-winners. But yields today are too darn low to allow continuation of that trend. Inflation Protected ETFs are perfect on paper, but protection from future rising prices can be expensive (in the form of very low yields): Don’t count on a free lunch and don’t invest in these ETFs unless you are willing to make a thoughtful, credible assumption that inflation risk is significant enough to compensate you for the low yield. Mortgage Backed fixed income offers higher returns on paper because of less perfect credit quality (securities involving GNMA are government insured but others are not and are currently protected by the goodwill and choice of Uncle Sam). But with rates still at levels that range between extremely low and ridiculously low, borrowers remain incentivized to refinance. That means many instruments will continue to be cashed out earlier than the initially stated contract dates, and thus force funds to reinvest cash at lower current rates — thereby suggesting lower future dividends to shareholders.

That brings us to Corporate issuers.

Until the economy gets on much firmer footing than is the case now, I suggest extreme caution with resect to High Yield (“Junk”) Bond ETFs. As a former junk-bond mutual fund manager, I know full well how the impact of recessions here is a lot more painful in real life than academic studies lead one to believe. (Don’t think about default rates: Many of the worst losses stem from term restructurings that precede and often prevent the occurrence of a bona fide legal default event. So published default rates drastically understate the level of risk.) Also, potential crisis-related liquidity problems tend to be more painful for High Yield.

Investment-Grade Corporate is the mainstay for those who are unwilling to accept the skimpy yields on credit-risk free Treasuries. Credit risk is present and we do have to particularly think about it given economic uncertainty. But it takes a lot of financial strength for companies to get rated investment grade (those whacky derivatives from circa 1998 and 2008 are another story and a colorful chapter in Wall Street history) and those ETFs are very well diversified. We can work with quant signals (see below) to alert us to the needs to swap out of a particular ETF that may be seeing too many credit downgrades.

Step 4: Think About Yield

Fixed income yields typically won’t match what can be found among dividend-oriented stocks. The choice in this asset class relative to equities, is about risk; less price volatility for fixed income and less risk of income suspension or discontinuance.

I tend to start by sorting yields from high-to-low, but calm down: I never simply pick from the top, which is where the risk is usually highest. I’ll look at and sort based on other things too (see below).

We must also take all published yield numbers with a grain of salt.

As time passes, ETFs tend to roll over their portfolios as securities mature and/or as securities get too close to maturity to fit within the ETF’s targeted term. In other words, an ETF like the iShares 3-7 Year Treasury Bond ETF (IEI) (ETF Home) is going to have to sell some of its shorter term instruments as they get close enough to maturity to pull the overall portfolio to a maturity range shorter than the targeted 3- to 7-years. But nowadays, income streams from the newly purchased securities are much less than those of the older securities that were purchased when rates were higher and which just had to be sold.

The widely reported database yields are based on payments actually made. As of this writing, the published yield for IEI is 1.40%. But the current 3- and 7- year Treasury rates are at 0.16% and 0.47% respectively. While the entire portfolio is not going to be rolled over today, there are still likely to be enough that are replaced with new purchases commending lower rates than the securities sold, which means that unless and until rates rise, we have to prepare for dividend reductions.

There’s also a metric known as SEC Yield that ETFs must disclose. It’s based on a mandated formula reflecting income netted over the past 30 days). For IEI, it’s 0.14%. Don’t panic if you own IEI. The SEC Yield is no more the last word on the topic than is the typically published yield based on actual dividends recently paid. It’s unlikely rates will stay long at current covid-level extremes. Therefore, it’s not sensible to assume IEI’s entire portfolio will indefinitely be cashed out and reinvested at these levels. So we can assume, under today’s market conditions, that IEI’s SEC Yield is unrealistically low in terms of what an investor who buys the ETF today can anticipate.

But we do have to anticipate some additional reductions in payout. To provide a sense of the rate at which the dividend could slide, consider that that the eight monthly per-share dividend payments IEI made between 2/7/20 and 9/8/20 were, from oldest to most recent: $0.1985, $0.1808, $0.1624, $0.1254, $0.1244, $.1136, $0.1150 and $0.106.

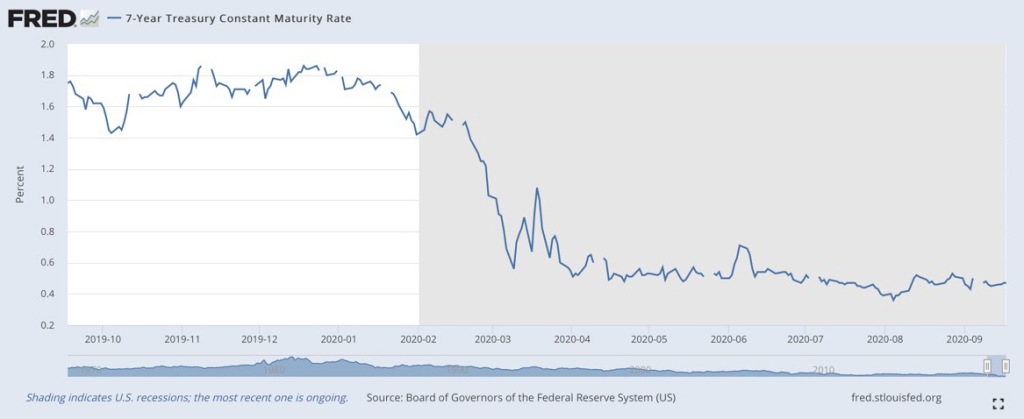

The good, if we want to call it that, news is that there’s not much room left for rates to fall. The table below shows, as an example, recent trends in the 7-year rate:

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US), 7-Year Treasury Constant Maturity Rate [DGS7], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DGS7, FRED chart updated Sep. 18, 2020

If the 7-year rate stays where it is indefinitely (and assuming the 3-year rate does likewise), we would have to assume that IEI’s dividend payout would trend toward a level that’s represented by the paltry 0.14% SEC yield. The FED’s recent determination to refrain from raising rates until 2023 does put that sort of consideration on the table. But even so it’s extreme. We have to expect more roll-offs and replacements of portfolio holdings, but 2-3 years isn’t likely to be enough to get the actual dividend down to the level presumed when calculating the SEC yield.

For now, with rates likely to rise just a bit to less-extreme but still historically noteworthy low levels. Without making pretenses about the levels of precision we can achieve, I suggest investors mentally subtract at least 0.50% from published yields.

Step 5: Use Chaikin ETF Power Ranks

This is where the rubber meets the road since our model is forward-looking. Using technical analysis for Fixed-Income ETFs, we work with long- intermediate- and short-term tests with an emphasis on the former. Our approach aims to detect and follow trends, rather than looking for reversals in direction. (Click here for a “White Paper” that explains our model in more detail, including the rationale for using technical analysis to evaluate ETFs.)

As a trend-following model, our Power Rank is subject to the challenge faced by all such models for all asset classes; detecting changes in trend. This is why its important to make choices about and pre-filter based on the first four steps. Rather than naively follow rank, it’s preferable to look for the best ranks you can find among the group of ETFs that satisfies your Yield, Issuer and Term choices. Also, consider Rank in connection with Risk (see below).

Our Ranking approach assesses ETFs two ways:

- One is through a Very Bullish-Bullish-Neutral-BearishVery Bearish rating which is based on where on a best-to-worst scale a U.S. Fixed Income ETF falls relative to others in this category.

- The other is a more granular “Group Rank,” which shows the ETF’s position (1 is best) relative to other fixed-income ETFs classified as being in the same group.

Step 6: Consider Risk

There are usually many fixed-income ETFs with good Power- and Group-Ranks to choose from even after having considered Yield, Issuer and Term. So there’s much to be accomplished by doing what every investor ought to always do anyway: Asses risk.

One determinant of fixed-income risk is credit, but that tends to be fairly stable and best managed by the type of issuer one seeks (i.e. Treasury versus Investment Grade Corporate versus High Yield/Junk).

Over the course of time, term/interest rate risk tends to be the major consideration. This involves:

- Maturity: This is the amount of time left until the securities reach their contractual payoff or “call” dates.

- Duration: This esoteric metric combines maturity and coupon size (the potential to earn interest on interest). So high-coupon bonds, which have shorter durations, allow interest on interest at escalating rates to more than offset lower face values thus being preferable in rising-rate environments.

- Convexity: This even more esoteric metric speaks to the relationship between changes in duration and changes in interest rates. (Now you may be starting to see how Michael Bloomberg, whose terminals were early leaders in this sort of crunching, got rich and why fixed-income portfolio managers can sound so geeky when they talk.)

Good news: We can and will skip the fancy stuff and engage with all this through the way these factors impact ETF portfolios. We understand that longer maturities and duration increases the risk of future price declines to to higher interest rates (subject to potential modification from positive or negative convexity) and that this ultimately manifests (1) through greater ETF price volatility, and/or (2) through higher Betas, which measure an ETF’s volatility relative to a representative benchmark — we use the iShares Core U.S. Aggregate Bond ETF (AGG) — with 1.00 suggesting average relative volatility/risk and higher or lower Betas indicating more relative risk.

Details aside, just know that higher Volatility/Beta means higher downside risk from rising rates.

Step 7: Be Aware Of Assets Under Management (AUM)

This impacts ETF holders two ways.

- One is that smaller funds find it harder to cover fixed costs meaning expense ratios are likely to be higher all else being equal. (If a small ETF has a low ratio, chances are the issuing company is subsidizing the some of the expenses.) But as I’ll discuss below, I won’t obsess over this.

- The other issue, the one that needs to concern us, is commercial risk; the possibility the sponsor firm will decide the ETF’s commercial prospects don’t justify continuing existence. It’s OK if an ETF liquidates; the money shows up right away in holders’ brokerage accounts and is usually recorded as a sale. But it is important that a liquidating ETF be able to get fair prices for the securities it sells. This is rarely a worry with U.S. equity ETFS, that tend to avoid excess obscurity. But fixed income securities don’t trade as frequently. So although some of the smallest ETFs I see look intriguing, I am willing to let tiny AUM scare me away. (Note that in extreme flash-type circumstances, even the best fixed income ETFs can be temporarily impacted by liquidity issues.)

Investment grade corporates, though they don’t trade daily, can attract buyers if sold outside the context of a market crisis that impacts everything. So we can be open to small ETFs, but not those at the extremely small levels. Liquidity problems with respect to portfolio holdings, can, however, be severe if things go wrong in the High-Yield (Junk) market segment.

Step 8: Consider ETF Expense Ratios — If You Want To

Commentators love to wax poetic about expenses, and management fees that drive them, and express outrage at anything more than minimum levels. I’m a rebel, though, and don’t play this game.

All ETF returns are presented net of fees (these are fund expenses that are subtracted before arriving at fund net income, which is what gets paid out to shareholders). If a higher-fee ETF outperforms a lower-fee rival, then I’m fine with the fee: It means the higher-fee managers are earning what they get. So in essence, I let marketplace dynamics address the fee issue on my behalf.